OUR NAMESAKE

Walk through the neighbourhood of Bannerman Park in downtown St. John’s, and you’ll see historic merchant buildings – ranging from stately to modest – framed by mature broadleaf trees. Views of these mansard-roofed homes embellished with ornamental mouldings are bordered by mature gardens, decorative iron fences, and towering chestnut trees.

These architectural details have become synonymous with the island portion of Newfoundland and Labrador. But these prominent surroundings have origins in a tragic chapter of the city’s history.

On July 8, 1892, a large portion of downtown St. John’s was destroyed by fire. Aptly known as “The Great Fire” – in its ashes, the Second Empire architectural style flourished. Spurred by one of the architects tasked with rebuilding the city, John Southcott, the familiar building style of downtown St. John’s has become known locally as “Southcott Style.”

DRAWING iNSPIRATION fROM a pLACE aND a mOMENT iN tIME

The 19th century was a period of far-reaching change during which several artistic and architectural movements emerged – one of those being the Arts and Crafts movement. In opposition to the perceived low quality of machine-manufactured goods, the Arts and Crafts movement is associated with finely adorned ceramics, wallcoverings, furniture, and textiles.

An interesting feature of the Arts and Crafts aesthetic is that many of its proponents were trained as architects. While the movement was not defined by a single style, the commonality of its founders lent itself to the one defining feature of the movement – creating cohesive, harmonious interior spaces across a wide range of disciplines. These disciplines included textiles, wallcoverings, artwork, furniture designs, and architecture, united by a sense of resonating permanence and beauty. William Morris is a designer whose work, particularly in wallcovering design, has become synonymous with the movement – he believed in the importance of creating high-quality objects and interior spaces that were beautiful and functional. Other prominent designers of the period include May Morris, founder of the Women’s Guild for Arts and William Morris’ daughter; and Agnes Northrop, a prominent American glassworks artist who worked with Tiffany Studios.

A typical rural home in Burin, Newfoundland and Labrador, that features a Mansard roof – one of the defining features of Second Empire Architecture.

At around the same time as the Arts and Crafts movement, Second Empire architecture was establishing in France. This style’s namesake is the Second Empire of Napoleon III of France, who, in partnership with the architect Baron Georges Hausmann took on a public works programme that transformed the city of Paris in less than two decades. This urban renewal program resulted in the creation of elements now synonymous with France’s capital city – the New Louvre (a classic example of Second Empire architecture), widened boulevards, stone apartments, and parks and squares featuring green spaces in the heart of the city.

Second Empire style soon began to proliferate in Canadian commercial and residential buildings. Implementing elements of Italianate and Romanesque design, it lent a sense of permanence, weight, and opulence to structures. The concurrent revival of Baroque and Italianate styles seen in Second Empire architecture, paired with the Industrial Revolution, had a profound impact on the decorative arts.

In Atlantic Canada, the widespread use of wood as a building material is seen in the Second Empire homes in the region; characterized by narrow wooden clapboard, three-sided ground floor bay windows, and lavishly carved woodwork. Door and window surrounds feature decorative wooden cornices, attractive details on eaves, and well-turned wooden decoration and mouldings. The plain, economical design of many wooden homes built in outport Newfoundland during the 19th and early 20th centuries may seem to have little in common with the richness of Second Empire tradition, but the prevalence of the mansard roof is an indicator of the lasting mark that this architectural style has had on the region.

THE GREAT FIRE OF 1892

On a hot summer’s day, on July 8, 1892, a large portion of downtown St. John’s, NL, was destroyed by fire. This was the third 19th-century fire to gut the city. Dubbed the “Great Fire”, it was economically and socially devastating. Two thousand houses were destroyed and about 11,000 of the city’s 30,000 people were made homeless. Reports at the time indicate that the fire began from a single match thrown in a stable at the intersections of Freshwater and Pennywell Road; a northwest wind then swept the flames across the city. Temporary shelters were erected, and many of the houseless relocated by way of train to Harbour Grace and Conception Bay.

THE ORIGIN OF SOUTHCOTT STYLE

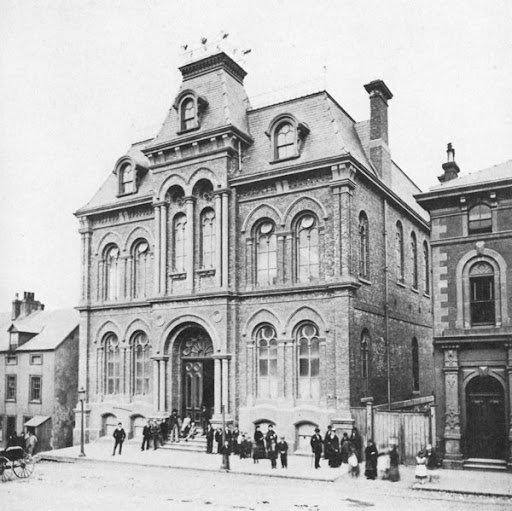

The Athenaeum, built by James Southcott, burned in the great fire of 1892.

While Second Empire Architectural style had already begun to set root in the city when the Great Fire occurred, the partial destruction of the area allowed it to flourish. John Thomas Southcott – whose father, James, had constructed structures such as Devon Row and the Athaneum – was part of a prominent family of architects who emigrated from Exeter, England in 1847. When they landed in St. John’s, it was namely to help rebuild the city after the fire that occurred in the same year that they emigrated. Not only did the headquarters of the architects burn in the Great Fire of 1892, the Athenaeum did as well – this former cultural centre of the city was Romanesque in design and featured a lecture theatre, stage, and library.

Many of the homes designed and rebuilt on Gower Street and Monkstown Road – including the historic Southcott House in which Southcott lived – were influenced, if not built by the Southcotts. The style’s influence on the city can be seen not only in residential homes in old downtown St. John’s, where half of the buildings fall into the “Victorian Mansard (Southcott)” style, but in commercial buildings built long after the period ended – such as the railroad building on water street west and the new courthouse on Duckworth street, both erected in the 20th century.

This Second Empire design movement brought recognition to decorative art and artists during a period that sought to reconcile progress and innovation with tradition and historicism. Once you know the history of this architectural style, it’s hard to miss when strolling through the streets of downtown St. John’s. Rounded dormer windows and brick chimneys jut out from rooftops framed by dentils on eaves, elegant woodworks frame porches and doorways, and curved mansard rooves atop brightly-painted clapboard recall Renaissance and Baroque French architecture in a seemingly unlikely place. Second Empire has become the defining architecture of the capital city.